“Em Silêncio” is a comic strip by Adeline Casier that illustrates the “leap”, that is, the clandestine emigration to France of thousands of Portuguese during the Estado Novo dictatorship. Between 1957 and 1974, 900,000 Portuguese went to France and thousands crossed the borders without passports. This was the case of the author’s grandfather, whose clandestine trip to France is portrayed in the work and shows that the dramas of illegal immigration continue, only the nationalities of the protagonists have changed.

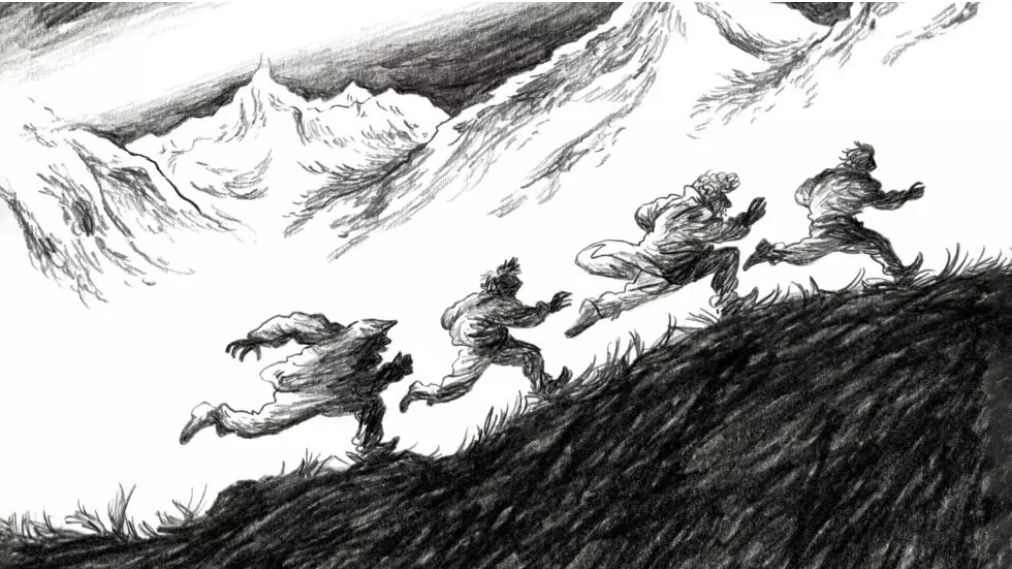

The story of “In Silence” begins with shots of men walking in a line somewhere in the Pyrenees mountains. It is November 1962 and poverty, lack of work and the threat of mobilization for the colonial war force João to leave his daughters and wife in the village of Arnozela, in the north of Portugal, to seek support in France. João goes in search of a better life and embarks on a journey into the unknown after paying a smuggler. His story echoes those of so many thousands of Portuguese who lived it and those of so many others who today repeat it from other countries.

“Through my grandfather’s story, I hope that readers can identify with a more universal story, that of illegal immigration” , says the author, who begins by explaining the title “In Silence”.

This story is based on my grandfather's testimony, but I created part of it. There is a character that I invented and who was not part of his testimony. There are also scenes that I added for narrative purposes and for the plot. In any case, what came up a lot in his testimony was that on this crossing that he made, there was this thing of always hiding, of not making noise, as if we had to be a little transparent... Hiding in farms, in rocks, in nature. And all because he crossed Spain on foot.

And then, 'In Silence' because, in my story, my grandfather was kind of ashamed of what he had experienced and there is a whole reflection around the fact that he had gone through all that to arrive in a country where he didn't necessarily feel comfortable or wasn't welcomed as he expected. It's like a broken dream. We expected to find a job straight away, have money, have a comfortable life and it ends up being a bit more complicated than that. Also in other migration testimonies, I heard a lot about the fear of telling the family everything that had happened, everything that had been experienced and that when they got there, it was difficult and there was a kind of disappointment.

It was at the age of 23 that Adeline asked her grandfather to tell her what he had experienced and now, at the age of 27, she is publishing the comic. The aim is not to make her grandfather a hero, but to show the universal and timeless dimension of emigration. Since she was a child, she has always heard her mother's stories, which include the image of her grandfather entering France hidden in a van loaded with pigs that were going to the slaughterhouse.

This is my grandfather's story. I asked him to tell me his story, how he arrived in France. It all started because my mother told me a small part of that story, which is about the moment when my grandfather had to cross the border between Spain and France. As there was a risk of customs checks, he hid in a pigsty truck with other people who were emigrating. They had to hide because that prevented customs from searching the trucks and also because they could stay warm because it was winter.

That's why I've always had this story in my head, since I was a child, and I wanted to know more. So I asked my grandfather to tell me his story and I decided to write a book. It's important to remember that stories of illegal immigration are very contemporary. Even though this story tells of experiences that may be very different from those of someone who migrates from an African country to France today, I think that there are huge difficulties in getting to this country and being welcomed properly, with respect.

There is still a certain "silence" surrounding the history of Portuguese emigration to France during the Estado Novo dictatorship. In recent years, the subject has begun to be discussed more in films, books and academic studies, and this has contributed to people starting to talk about it more within families, thanks in part to the curiosity of the younger generations who are searching for their roots. This is what also happened with Adeline.

In the past, people were afraid to talk. It wasn’t really fear, I would say that we didn’t dare talk about the difficulties of life, about when we arrived in the destination country and lived in poverty or it wasn’t what we expected. Maybe we were afraid of what others would look at us like, that they would say “that’s why they left the country”… And then there are many Portuguese people who had the impression that those people who left betrayed the country. Well, that’s what I heard, it’s not what I think, but that’s what I heard. I think that must have also contributed to the fact that people didn’t want to tell this story.

Furthermore, in France I often hear the phrase 'Ah, the Portuguese are really good workers, they never say anything, they never complain'. But I think it's super hypocritical to say this because it shows that the Portuguese didn't have the means to speak up and say what they felt or couldn't because if they did, the boss could tell them: 'Well, don't come to work tomorrow' and if there's no job, there's no papers. This put people in very complex situations where they had no voice. Writing this book was also a way of giving my grandfather a voice, of paying tribute to him and giving him the voice that he perhaps didn't have at that time.

He left Portugal because there was a Salazar dictatorship and because there were movements to take people to Angola and Mozambique. France then benefited greatly because many Portuguese people came to France knowing that the country had to be rebuilt after the war and that they would find work immediately. This was also the case for the Italians for a period and the employers benefited because they had cheap labor that could do difficult jobs.

The story of the grandfather and his travelling companions is a long journey that lasts nights and days. They walk for miles and miles, sleep in the open air and on farms, always hidden, at the mercy of the cold, the smugglers and the occasional solidarity of whoever they cross. Along the way, they lose track of time and space, there is hunger, torn shoes, encounters and missed encounters. The contrasts of the black and white drawings accentuate the interior and exterior landscapes that accompany the characters.

I really like working in black and white. I tried working in color, but it didn't work. Black and white and the contrasts that I can achieve with my pencil also allow me to use these gray environments as a tool for storytelling. In fact, it's not just about giving the atmosphere of a scene, the light, it's also the way I tell a story, how I can intensify the emotion of a character, for example, or highlight an element graphically to reinforce something. In fact, my black and white, my contrasts are a graphic tool for storytelling.

As my grandfather told me his story, I wanted to be able to transcribe his feelings through narration. At a certain point, there was really a sense of wasted time because he constantly had to cross mountain paths, valleys, and hide… Sometimes he could be rescued by a smuggler in the middle of the night or at completely random times because it was dangerous and perhaps it would be better to cross at night because there was less risk of meeting people or because the smugglers could only arrive at that time - often they were people who were doing other things at the same time.

My grandfather told me that when he made the crossing, there were people who didn't make it to the end.

There are also echoes of the “ torn photograph ” recalling the way in which smugglers were paid and in homage to the work of the filmmaker who best portrayed Portuguese emigration to France, José Vieira . We can also see the poverty of the shanty towns drawn from the images of Gérald Bloncourt, the French-Haitian photographer who also wrote a chapter in the history of this emigration.

Through my grandfather's story, I hope that readers can relate to a more universal story, which is that of illegal emigration (…) I hope that this can create a reflection on migration and on the view we have towards people we consider foreigners in our country. Well, I'm not sure that the word 'foreigner' is a good word because we may not have exactly the same cultures, but we are all human beings who feel things, who experience things and we are, in a way, all the same.

Just over 50 years ago, thousands of people fled Portugal, where they were deprived of everything, including the most basic necessities such as bread, health, education and freedom. The comic strip “Em Silêncio” reminds us that yesterday it was the Portuguese who crossed borders without documents and that today there are many other people who turn to smugglers and unknown routes in order to simply try to find a better life.